Translated Korean Women’s Literature and Representations of Resistance Through Digital Humanities, 1917-1961

INTRODUCTION

In 2018, when I was 18, I studied abroad in Seoul, South Korea through a government scholarship: the National Security Language Initiative for Youth (NSLI-Y). Every weekday I woke up at 6 AM and prepared to commute two hours from Anyang, a satellite city, to Ewha Womans’ University in Seoul. Right before the campus, where a cluster of makeup stores and stalls selling tteokbokki lay nestled, were statues commemorating comfort women. Back then, I had no idea what I was looking at, but knew it was something of importance.

I was in graduate school when I began returning back to these statues, which, by then, I knew depicted Korean comfort women from World War II. It was in a decolonization class my first semester of a master’s degree I began digging deeper into the subject of Japanese colonization in Korea, and after an independent study of literature from the period, I decided to turn this into my master’s thesis. For the thesis, I expanded the timeline from 1917 to 1961, as I wanted to examine the continued trends and themes across a broader sustained period.

This website is a culmination of the work I did for my master’s thesis, titled “Translated Korean Women’s Literature and Representations of Resistance Through Digital Humanities, 1917-1961.” In it, I looked at six short stories from Kim Young-hee’s collection Questioning Minds, which translated Korean women writers from the 1900s.

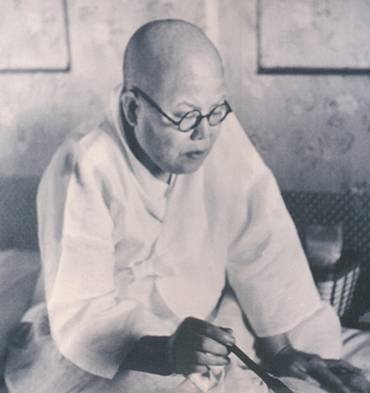

Six authors were represented in this study: Kim Myeong-sun, Na Hye-seok, Kim Won-ju, Han Moo-sook, Kang Sin-jae, and Song Won-hui. Three were active during the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), and the other three in the postcolonial period directly after World War II and the Korean War (1948-1961).

Throughout the research process, I utilized a text mining software called KH Coder to create co-occurrence networks of the six short stories I was looking at in translation. Co-occurrence networks analyze the relationship between words and phrases throughout the text that’s input into the system. With this information and academic texts, journals, and publications, I was able to argue that throughout each of the six short stories, these writers were subverting the stereotypes of women during the periods they were writing within through sustained methods, such as flipping the script on women’s suffering and the Korean notions of han, or suffering.

The following pages below introduce the research in a multimedia and accessible format, allowing others to access the research I conducted over the course of my master’s degree and thesis work.

Please click through the tabs below to learn more about the periods, writers, and the process of using KH Coder to create deeper analyses of these stories.

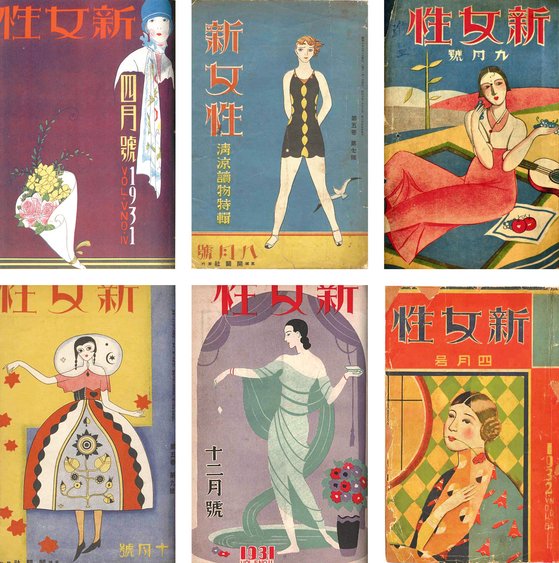

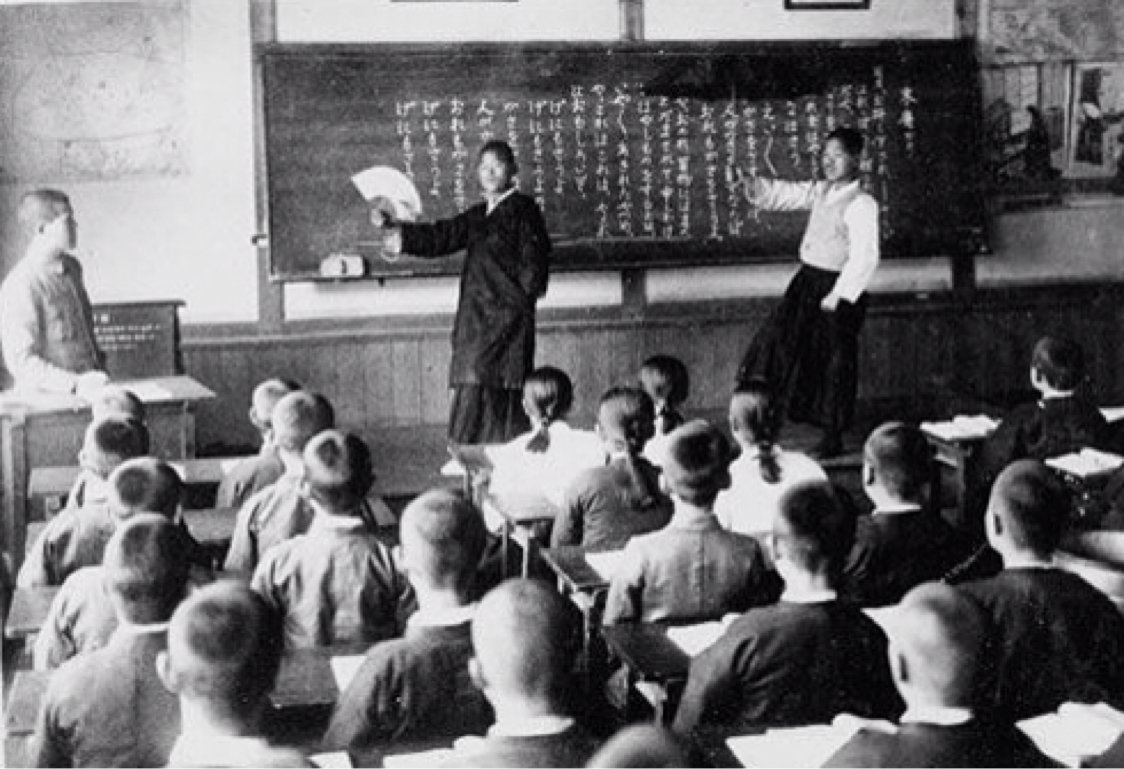

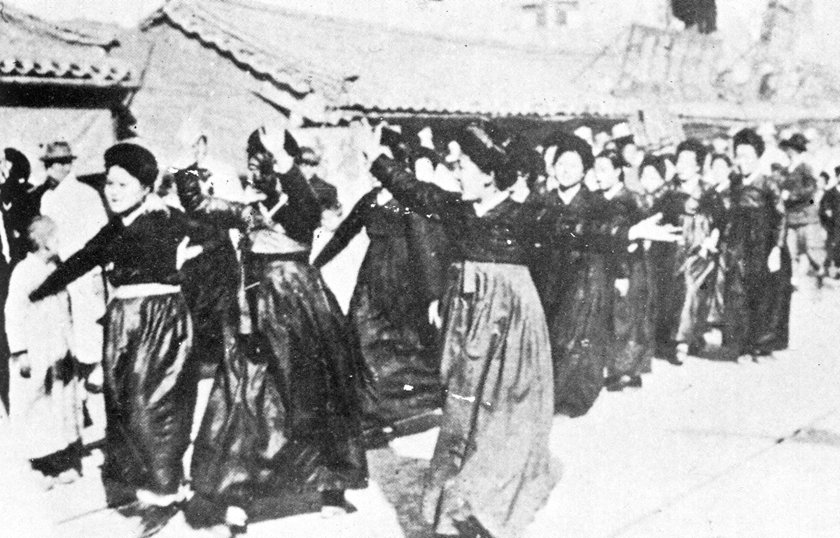

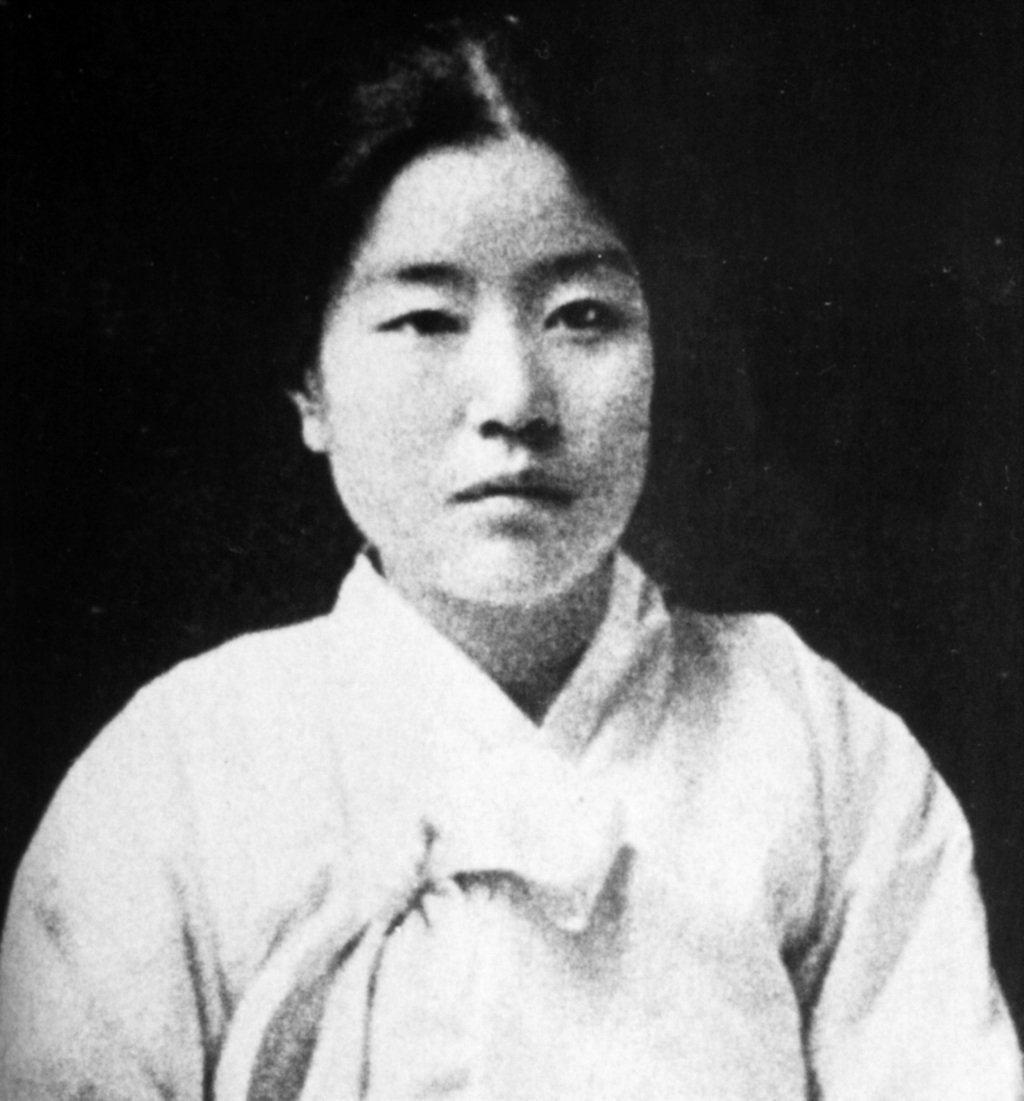

Image Credits (above; from left to right):

Han Youngsoo – International Center of Photography

By Unknown author - 나혜석 시, 소설 경기도 수원 1896-1948 1915년 등단, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19170257

Somyeong Publishing Company

Unknown