한무숙 | Han Moo-sook

Biography

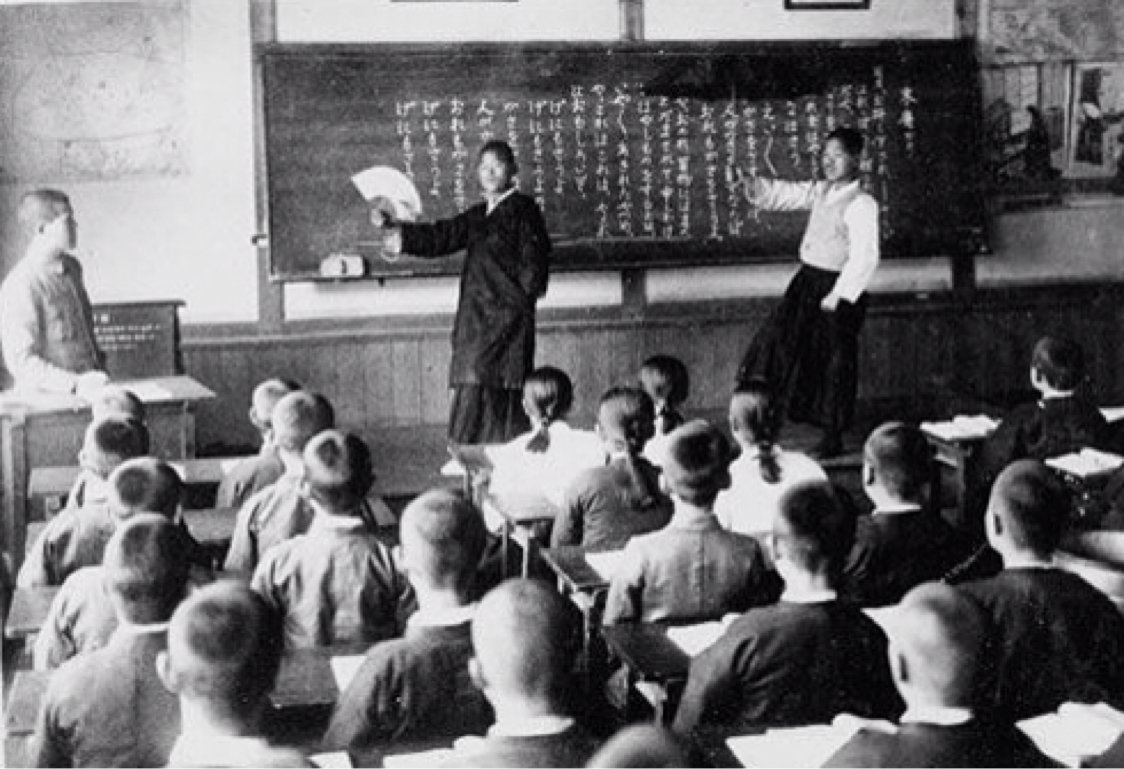

While several women from the colonial period were publishing their first short stories in the late 1910s, Han Moo-sook was born in 1918 to an educated family. Due to this, Han attended school in Korea throughout her primary and teenage years. Her parents cultivated an artistic lifestyle for their daughter by allowing her the chance to take courses in Western-style painting and, when she was at home from school due to chronic poor health, access to Western classics translated from Japanese.

Inspired by the books she had read as a child, Han would debut as a writer in 1942, amid the chaos of World War II and Japanese colonialism in the Korean peninsula. By then, she had married into a conservative Confucian family and just gave birth to her daughter, but her Japanese-language novel gained acclaim. It would be several years before she published another novel, after which Korea became independent, and Han became known as a dramatist and playwright, winning even more accolades for a different medium of writing.

However, one of Han’s biggest motivators as a writer came from her marriage, and how deeply interwoven the traditional Confucian expectations of her in-laws and a patriarchal society impacted her as a woman and a writer. Her writing career is indicative of the more Western-based education she received in her childhood home. At her career’s beginning, she did not have an attachment to the colonial-era literary organizations and magazines established, she kept her success a secret from her husband’s family, and her literary education largely found its foundations in the classics she had devotedly read as a child.

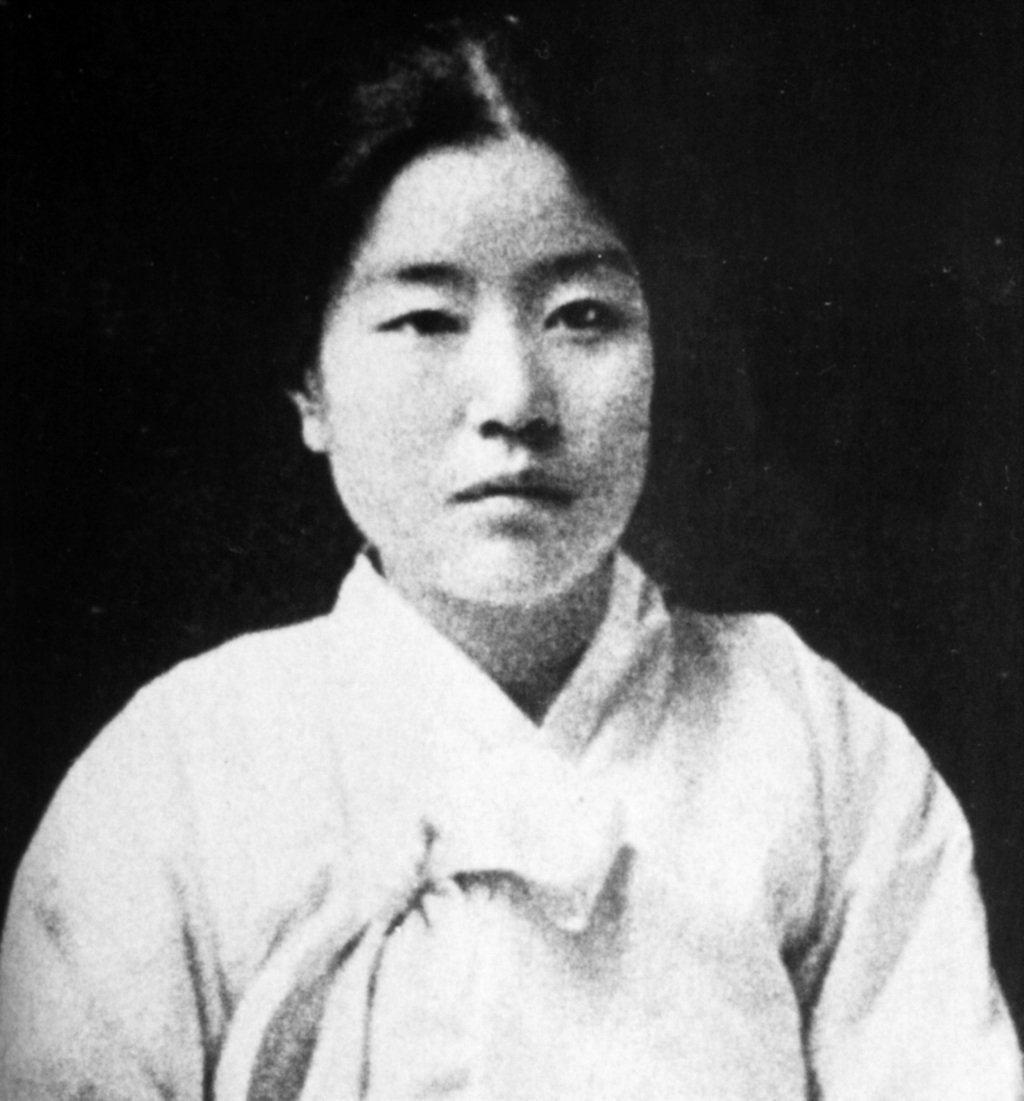

This marks her career’s rise as mirroring her male contemporaries more than female ones, and distinguishes her from her feminist predecessors, as writers like Kim Myeong-sun, Na Hye-seok, and Kim Won-ju found their roots and beginnings in communities established by women. Young-hee Kim defines Han’s legacy as often being associated with a traditional and upper-class culture in postcolonial Korea, but also offers an alternative look at her work: she straddled modernity and traditional culture, navigating in-between spaces through the perspective of women.

Image Citation: Unknown / via GW

Key Dates:

1918 - Han is born in Seoul

1941 - Han marries, wins first prize in a national novel writing course

1943-1944 - Han gains acclaim and wins awards for her playwriting

1948 - Han wins an award for her first novel

1949 - The short story “Hydrangeas” is published

1993 - Han passes away; she was in her mid-seventies

Hydrangeas

The narrative of her 1949 short story “Hydrangeas” reflects the themes Han dwelled on throughout her literary career, which navigated these spaces. The main character of the story is Myeong-hui, who, at the beginning, is marked as the perfect wife.

She goes out to the stores to prepare for the day and takes care of the garden that houses the beloved hydrangeas the story is named after. These hydrangeas are a source of pride in Myeong-hui’s home, as they were brought in when she got married, and she has taken care of them in the decade since.

Despite this heavy-handed metaphor and symbolism, Myeong-hui’s dissatisfaction becomes the story’s discourse. On a superficial level, she has the perfect marriage, much to her friends’ envy and the people around her. Her husband is successful, and they live an upper-class lifestyle in a liberated South Korea.

It is a pivotal moment towards the end when Myeong-hui spots her husband with another woman, shattering the beliefs she held about her marriage and husband. This fuses together with the questions she has about her own life and purpose, especially as she ponders what’s next when the inevitable divorce with her husband finally occurs.

Image 1: unknown photographer

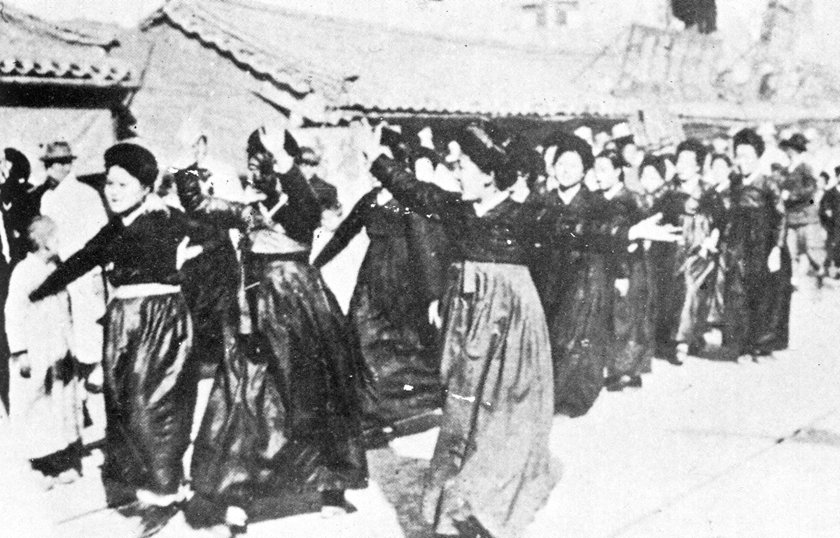

Image 2: unknown photographer

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis Through KH Coder

In the figure above, 17 subgraphs were generated within the co-occurrence network from KH Coder. Subgraph one, which is the largest cluster in this network, shows the connections between the domestic space, the people coming in and out of it, and how significant the hydrangeas are to the story. On the other end of subgraph one, Myeonghui’s heartbreak at her husband’s infidelity is broadly connected to “married” and “life.” Subgraph eleven shows the connection between Myonghui and her husband, while subgraph two, the other large cluster within this group, exemplifies the significance of actions, such as marriage.

An intrinsic link between Myeong-hui’s life and her husband is apparent without the help of a text mining software, and it happens to be a direct aspect of the story. Through KH Coder, the words “husband,” “Myeong-hui,” and “be” are all linked together with coefficients of 0.17 and 0.16, demonstrating how woven together these characters are in Myeong-hui’s story. The concept of the home being tied to a female protagonist also manifests directly in “Hydrangeas.” Myeong-hui has meticulously constructed her home and life inside her mind, and although it is mentioned how she goes out to get ingredients and has a maid, there’s a direct connection in the co-occurrence networks about home as a place of waiting. In one large cluster of interconnected words, the most revealing ones are “wait” and “home,” implying that the home is a place of anticipation for Myeong-hui.

With “heart” and “break” at the other distant end of the cluster, a domestic space, once a space where she was content, has become stagnant, a point of her suffering by the end. As evening falls and the hydrangeas, once a thriving symbol of a new marriage, flutter under the moonlight, Myeong-hui can recognize the limitations of the life she has been living, forcing her to confront the realities of what will happen next. Unlike Kim Won-ju’s or Na Hye-seok’s protagonists, Han leaves behind an open ending in this story, leaving behind lingering questions about her protagonist’s fate.

However, “break” is tied to two other distinct words: “know,” featuring a coefficient of 0.15, and “married,” which also has a coefficient of 0.14. “Know” implies a partition between past and present; its definitive nature creates a ridge between Myeong-hui and her husband. There is no going back with what she knows, although there is an alternative option for her where she pretends to have not seen anything.

“Break” appears in various forms throughout the text, whether in past or present tense, but mainly through conversation with Myeong-hui’s friend Cheong-sun. Regardless, despite it appearing mainly at the beginning, this is a narrative about breaking. Not only is the protagonist slowly breaking down the systems in place and unraveling the truth, but there is also a metaphorical break between her past and present way of living.