송원희 | Song Won-hui

Biography

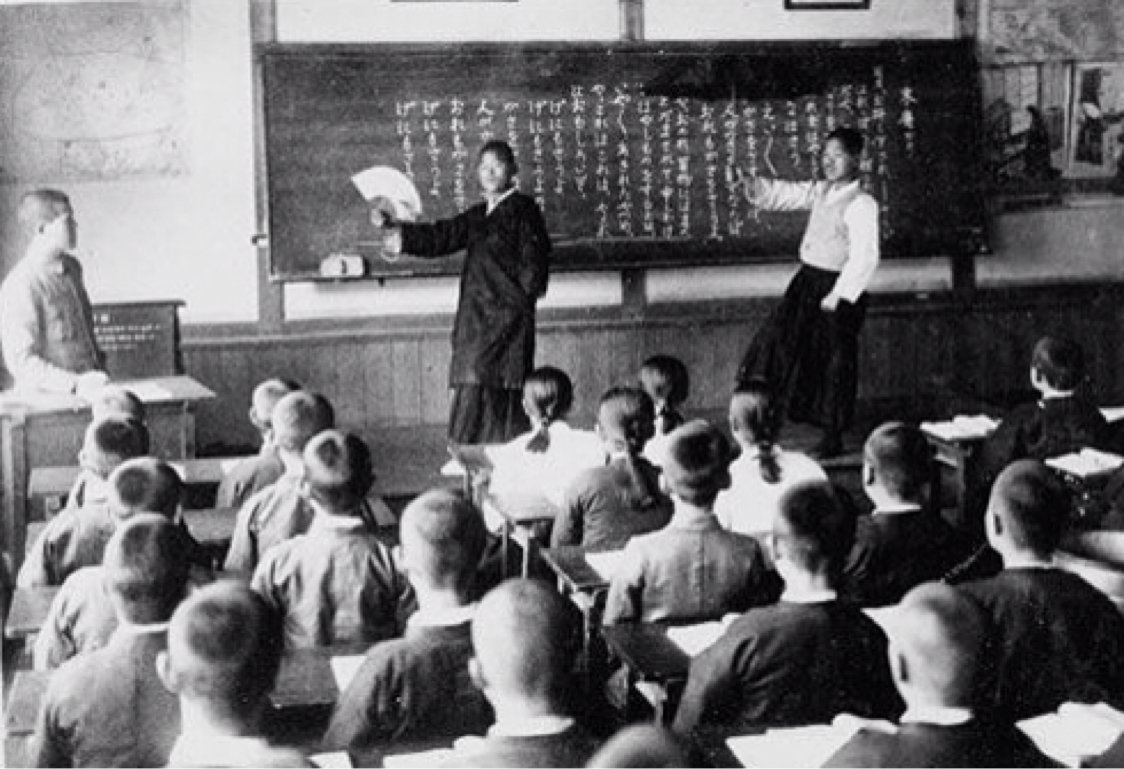

Like Han Moo-sook and Kang Sin-jae, the writer Song Won-hui was born in the mid-1920s during the Japanese colonial period. The daughter of a Korean independence activist, when she was eleven years old the family was forced to flee to China in an attempt to escape the Japanese colonial government and Song’s father’s potential arrest.

It was this upbringing, as well as the literary influences Song was exposed to during the seven-year period where her family was in exile, that would shape the work she would produce as an adult. Despite the Korean War, Song attempted to pursue her education at Gyeongju’s Tongguk University but ultimately ended up not being able to finish her schooling due to a lack of finances. However, being denied an education due to her family’s financial strain did not stop Song from pursuing a literary career.

When Song was forced to drop out, she published her first short stories in 1956. Her work after this, largely popularized by her novels, honed in on the ramifications of Korea’s contemporary history, showing how ordinary people were impacted by war and trauma. This puts her in conversation with several other female writers within her time: the Korean War and Japanese colonization had its lasting effects on women’s writing during this period.

In some of her most famous works from later in her career, published in the nineties, Song dwelled on her familial history in China, returning to the places Korean resistance fighters frequented. Several of her novels focused on the independence activists and fighters who fled abroad to continue their advocacy for an independent Korea. Like Kang Sin-jae, she, too, became a president of the Korean Association of Women Writers, and would later serve on the organization’s board.

Image Citation: Unknown / via Naver Cafe

When Autumn Leaves Fall

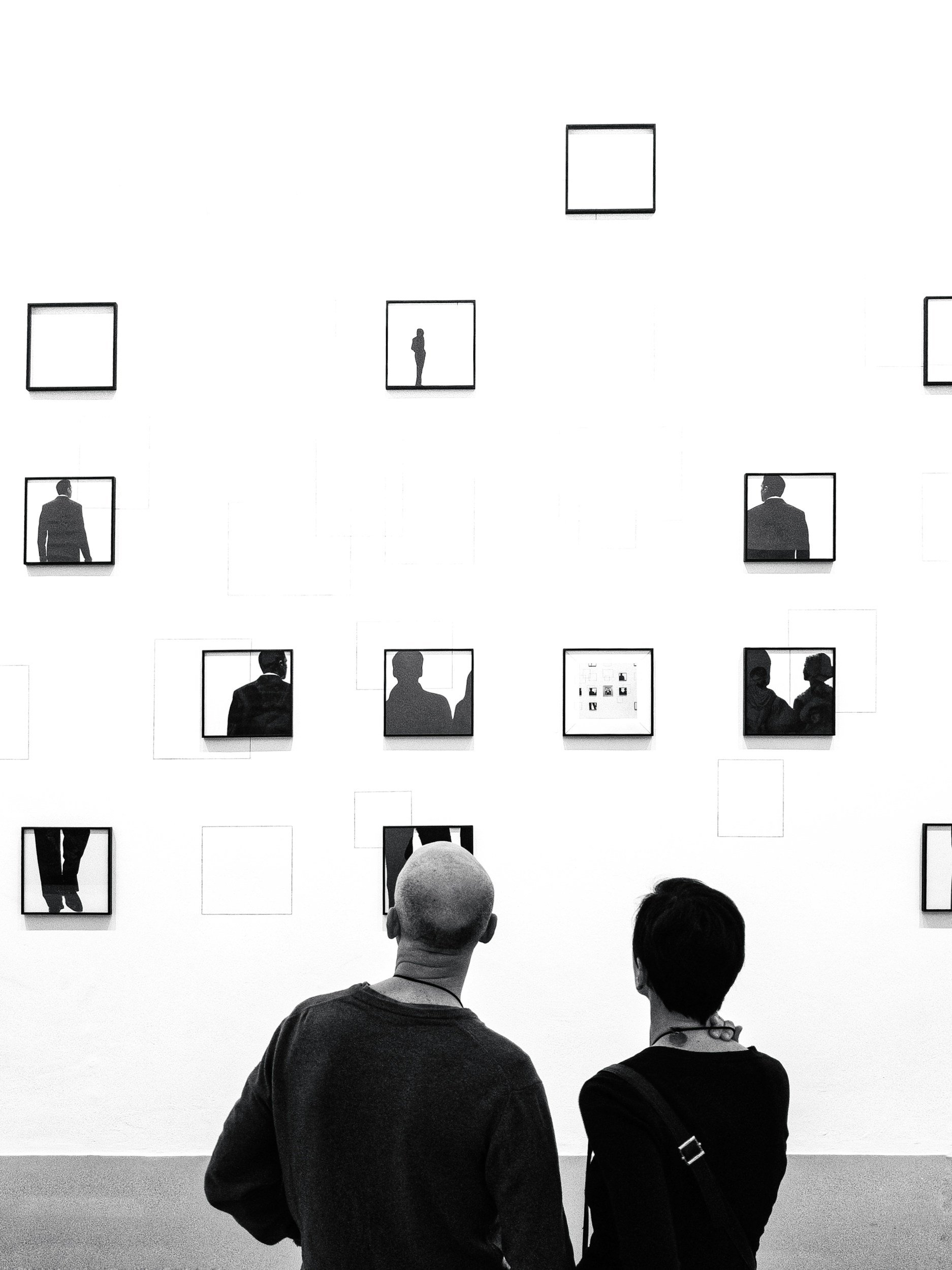

“When Autumn Leaves Fall” was published originally in 1961, eight years after the Korean War’s conclusion and the same year that Park Chung-hee officially took on the title of South Korea’s President. The story’s protagonist is Haryeon, who is in her forties and works as a painter. Married and having just turned 40 years old, she wanders the halls of the national gallery, as one of her paintings is being showcased there.

Throughout the story, as she takes in the work of other artists and reflects on her own practice and life, her anxieties about being a painter and artist, especially as a woman, clearly come to the surface.

This makes “When Autumn Leaves Fall” a piece very much about the process of introspection and reflection how Korea was shaped by not only the Korean War, but colonialism as well. Its protagonist considers her generation and herself as drifting through their lives due to the trauma of these major events; through KH Coder, it exposes itself through the connections between “lose,” “sense,” and “generation.”

Although this is a short story published in 1961, Song’s upbringing during the colonial period and its impacts plays a prominent role in the latter half of the story.

As Haryeon meets up with her first love, a man who, like many other Korean intellectuals during the postcolonial period and the severance of Korea into two different countries, defected to North Korea, her own education, which happened during the twilight years of Japanese colonization, and how she stayed in Korea becomes a point of comparison between the two artists.

However, there is a key difference between the two, even though they come from similar backgrounds and were educated in Japan: he is a man and she a woman.

Image 1: Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid

Image 2: via Unsplash

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis Through KH Coder

The figure above consists of 26 subgraphs, the most out of the co-occurrence networks created from these short stories. For “When Autumn Leaves Fall,” context is critical in understanding the results, as the co-occurrence network is more subtle. Subgraph one, which features the main character, her first love, and the notions of “be,” “not,” and “do,” exemplifies how connected they are, while also making these two characters into foils. Subgraphs six and ten reflect the sentiments on the passing of time and aging, especially within the context of a female protagonist.

Throughout the story, as she takes in the work of other artists and reflects on her practice and life, her anxieties about being a painter and artist, especially as a woman, clearly come to the surface. This makes “When Autumn Leaves Fall” a piece very much about the process of introspection and reflection on how Korea was shaped by not only the Korean War but colonialism as well. Its protagonist considers her generation and herself as drifting through their lives due to the trauma of these major events; through KH Coder, it exposes itself through the connections between “lose,” “sense,” and “generation.”

Although this is a short story published in 1961, Song’s upbringing during the colonial period and its impacts play a prominent role in the latter half of the story. As Haryeon meets up with her first love, a man who, like many other Korean intellectuals during the postcolonial period and the severance of Korea into two different countries, defected to North Korea, her education, which happened during the twilight years of Japanese colonization, and how she stayed in Korea becomes a point of comparison between the two artists. However, there is a key difference between the two, even though they come from similar backgrounds and were educated in Japan: he is a man and she is a woman.

While she might return home to her husband that night, believing that he was away on a trip when he is sitting there, simply reading a newspaper, KH Coder reveals some deeper connections worth exploring in its co-occurrence network. The words “arm” and “husband” are tied together with a coefficient of 0.12, although this physicality is only introduced twice through Haryeon and her husband towards the end. In each usage of the word “arm” throughout the story, it’s connected toward a man physically holding his arm out and holding a woman. Twice it appears in the form of the art being displayed, whether it’s a statue or a painting of a man holding a woman, once when Mr. Nokpong moves his arms towards the protagonist, and the two times in which Haryeon’s husband moves his hands to latch onto her neck and bring her towards him.

Not only does this create a sense of physicality and restraint, but it also creates a larger question, especially as Haryeon’s husband remains unnamed. He’s referenced fourteen times throughout the text, but not once with a name. He also does not appear towards the end and is associated with guilt as Haryeon realizes he was home this entire time. This is a stark contrast against how her first love is mentioned, as, despite the third person perspective utilized to propel this narrative forward, he’s mentioned by his first name over seventy times throughout the story.

Like several of the other stories, one key phrase appears in “When Autumn Leaves Fall” and its co-occurrence network. Directly tied to the name “Haryeon” are the following words: “be” (coefficient: 0.15), “not” (coefficient: 0.13), and “do” (0.14). Again, this reflects the broader sentiments of the period through the lens in which women should be expected to remain passive, especially as Haryeon returns home to her husband and begins to feel guilty for specifically seeking out the man she considers to be her first love and reminiscing about a past that has long since disappeared.

However, this is one of the story’s most compelling parts: the protagonist has a career as an artist, and her work is shown in a gallery. Although a critical part is her pondering about how her life has unfolded and casting doubt on its trajectory from here, there are no obvious references to how she is being held back by her husband. The only thing truly holding her back is the past and her connection to Choru, her first love, with the story ending on a somewhat positive note as she promises herself to work harder with her paintings and future.

The word “work” appears throughout the text 13 times within the co-occurrence network, but it does not hold a largely negative connotation outside of how Haryeon feels inferior compared to those whose art she is consuming at the beginning. The sculpture of the man holding a woman and child, which she stops to admire just as she begins strolling through the gallery, has been created by a new face on the art scene, one who is also a woman: Son Hyeson. Son, who is a recent graduate from an art school, becomes a source of admiration and comparison for Haryeon, especially when she begins comparing the new generation to herself.

And, like the other stories examined through KH Coder in Questioning Minds, “house” makes an appearance in the co-occurrence network, despite its connections only being in a subgraph with “seem” and “now.” When Haryeon first returns home from her trip to the gallery, her home becomes a different point of reflection. It is here the reader first learns she is unhappy with her relationship and situation. Her children no longer flock to her as she would like, and her husband has not only been going to the kisaeng houses, but he also acquired a mistress.

She hides the fact she is not happy with this, but it has begun to torment her. Perhaps this explains the connection between “woman” and “never” on the co-occurrence network, although there’s an interpretation of silence. As Haryeon wanders from one place to the next, only briefly returning to her home throughout the story, this is a broader echo of how her generation is drifting from one place to the next, simultaneously stuck in both the past and present.

This is a piece that straddles modernity and tradition, especially as the protagonist contemplates how she was trained in Western artistic practices during the colonial period, as well as the long-term impacts of what would become known as han. Not only is she personalizing and contemplating an entire generation’s grief, but she’s spinning it so that she can work harder and make art to compartmentalize and process her feelings in this new, but still patriarchal world she lives inside.