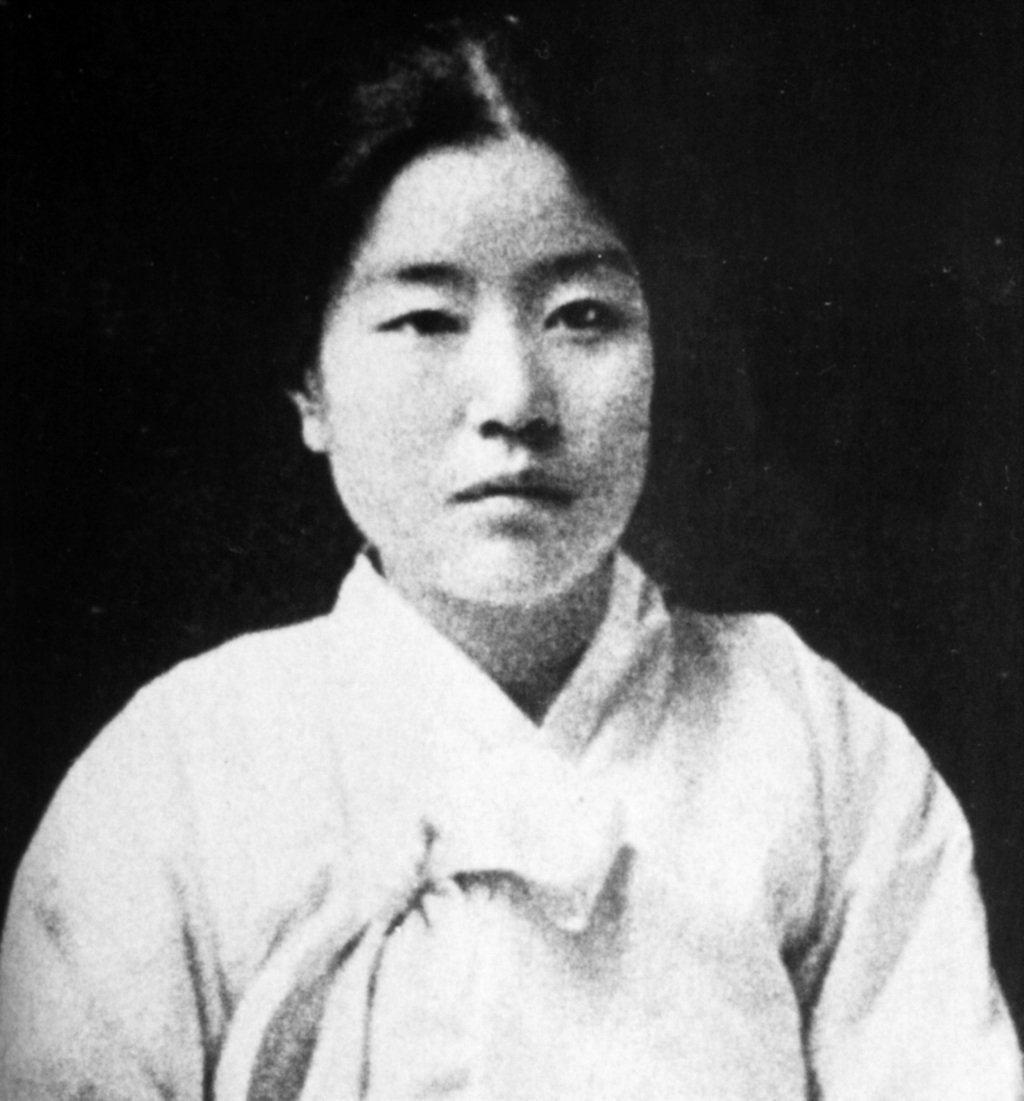

강신재 | Kang Sin-jae

Biography

Born in Seoul, raised in a province along the border of Russia and China, and briefly educated at Ewha Womans University, Kang Sin-jae embarked on a literary career after World War II had ended and the two Koreas were preparing for war. Her education and time at Ewha reflected a deep interest in literature: Kang had wanted to major in English but was forced to switch to home economics due to the Japanese colonial rule in World War II. As a child, Kang was encouraged to be a writer by her teachers and was even acknowledged by local literary awards for her work’s quality.

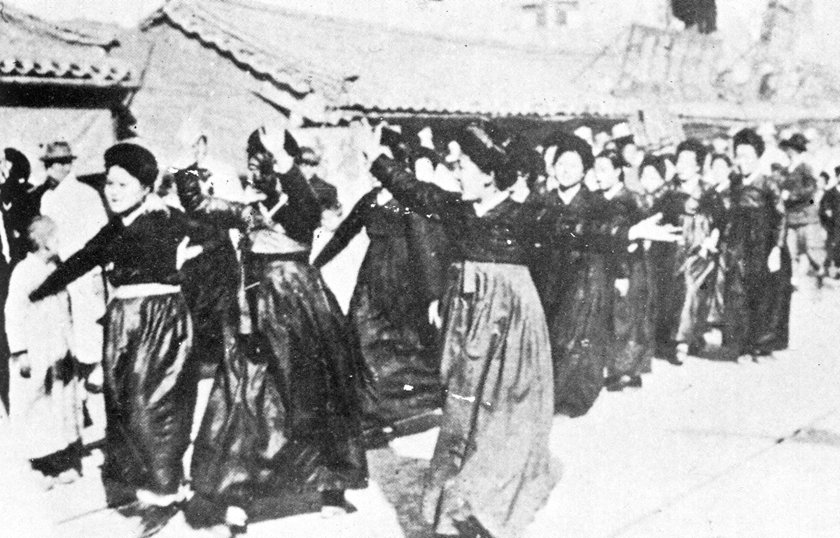

Her first short stories were published years later in 1949, and throughout her career, her writing explores the conditions of connection between people in moments of tragedy and strife. Kang was born during the colonial period, and many of her later stories took place with the Korean War as a backdrop, putting its characters under immense strain not only due to their personal lives but also because of the environments they are confined within. Despite this, her novels and short fiction often offer hope, as her characters grapple with love, desire, and joy in some ugly moments of war and brutality.

Kang continued publishing for several decades, shifting her focus towards historical novels and spearheading the Korean Association of Women Writers for several years as its president. By the 1970s, as South Korea was governed by the Park Chung-hee administration, Kang Sin-jae became the first Korean woman to be published in a multivolume collection. That was almost sixty years after “A Girl of Mystery” was published by Kim Myeong-sun, marking the beginning of contemporary Korean women’s literature.

Image Citation: Unknown / via Dong-ah Ilbo

Key Dates:

1924 - Kang is born in Gyeongsang

Early 1940s - Kang drops out of Ewha Womans University

1949 - Kang publishes her first two short stories

1959 - Kang is awarded the Korean Writers' Association Award

1970s - Kang is the first woman in Korea published in a multivolume collection

2001 - Kang passes away

The Mist

Although her short story “The Mist,” which was originally published in 1950, is not one of Kang’s most famous or well-known works of fiction, it reflects the themes and storylines she explored throughout her literary career.

Its protagonist is Seonghye, a housewife who, in her free time, has been writing short stories. “The Mist” begins with an extraordinary circumstance in her life not only as a housewife, but a writer as well: her work has just been published in a literary magazine.

Despite this remarkable achievement, which delights Seonghye at her success and because she received money for the story, her husband does not share the same satisfaction seeing his wife succeeding in the literary world.

He himself is a poet but lacks what it takes for his writing to stand out. Envious, he consistently puts her and her writing career down, ensuring his deep resentment and negative thoughts tramples her trajectory towards the top of the local writing scene.

Image 1: Susan Hanley / appeared first in The Korea Times

Image 2: 한영수 Han Youngsoo

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis Through KH Coder

Like several of the other stories throughout this research, the co-occurrence network in the figure above, specifically in subgraph 10, demonstrates the connections between the main character and existing within a space. Subgraph one, the largest cluster for “The Mist,” demonstrates the physicality and work of the language utilized, creating a dynamic that manifests in this visual example. Subgraphs two and three are examples of the notion of work and the home, showing Seonghye’s desire to create a writing career, as well as how other people can come to and from the home, but not her.

Through KH Coder’s co-occurrence graph, this shows the direct link between three different words within their own subgraph: “writing,” “hate,” and “try.” These words are connected by coefficients of 0.12, 0.12, and 0.20 respectively. However, the arrangement of these connections offers another interpretation: while “writing” and “hate” are connected, “hate” is also tethered to “my.” The story, which was published in 1950, would most likely reflect the gender dynamics in which Seonghye would instead simply be expected to just be a housewife.

The connection between “hate” and “my” could imply deeper tensions, one in which her husband wishes to reclaim his control within the household. He sees Seonghye pursuing a writing career, and being successful at it, as undermining his notions of masculinity. If his wife is successfully pursuing the career that he has been failing, he will do whatever it takes to ensure she will not continue. Although this piece was published not long after the colonial period, it echoes the expectations of women writers and how they were seen as inferior by their male literary counterparts.

Like several short stories examined throughout the research process, the verb “work” appears within its own subgraph in the co-occurrence network. Here, it appears attached to “bring” (coefficient: 0.18), “boy” (coefficient: 0.14), and “come” (coefficient: 0.12). However, unlike the other stories, this connection between “work” is subverted, showing that “work” is associated with young boys working for other people. This suggests when Seonghye is outside her writing world as a housewife, her life is quiet.

On a different subgraph, three other words are connected: “become,” “more” (coefficient: 0.12), and “job” (coefficient: 0.12). With the context of the story’s narrative arc, this becomes clearer: Seonghye brings up getting a job, but her husband’s pride rejects the idea of his wife working outside their home. At one point in the story, she even contemplates how she could keep herself busy within the home, implying that she really wants to do something and contribute to their finances.

However, it becomes more evident that Seonghye is an ambitious woman, as seen by the fact she was willing to submit to a literary magazine in the first place. But because she is stuck inside the home, which appears in its own subgraph with “day,” she becomes a victim of her circumstances. Perhaps if this short story had been written thirty years prior, taking on the thematic notes of Na Hye-seok or Kim Won-ju’s work, the main characters would have realized the impacts of the husband’s actions and actively resisted his expectations. But throughout the story, she remains silent. Again, this manifests with the connections between the words “silent,” “remain,” and “seat.” These are linked by coefficients of 0.33 and 0.22. “Remained” appears throughout the text seven times, and in six of those seven occurrences, it is associated with Seonghye not responding to someone else.

As her husband smokes imported cigarettes, writes poems that would not see the same success as his wife’s writing, and finds himself bouncing from job to job, Seonghye will be stuck in stagnancy, unable to break free of the confines of what “home” provides for her. While she is serious about her writing, he is not. Yet, at the same time, he chastises her for the writing style she uses and acts as if he knows better about craft simply because he was born a man.