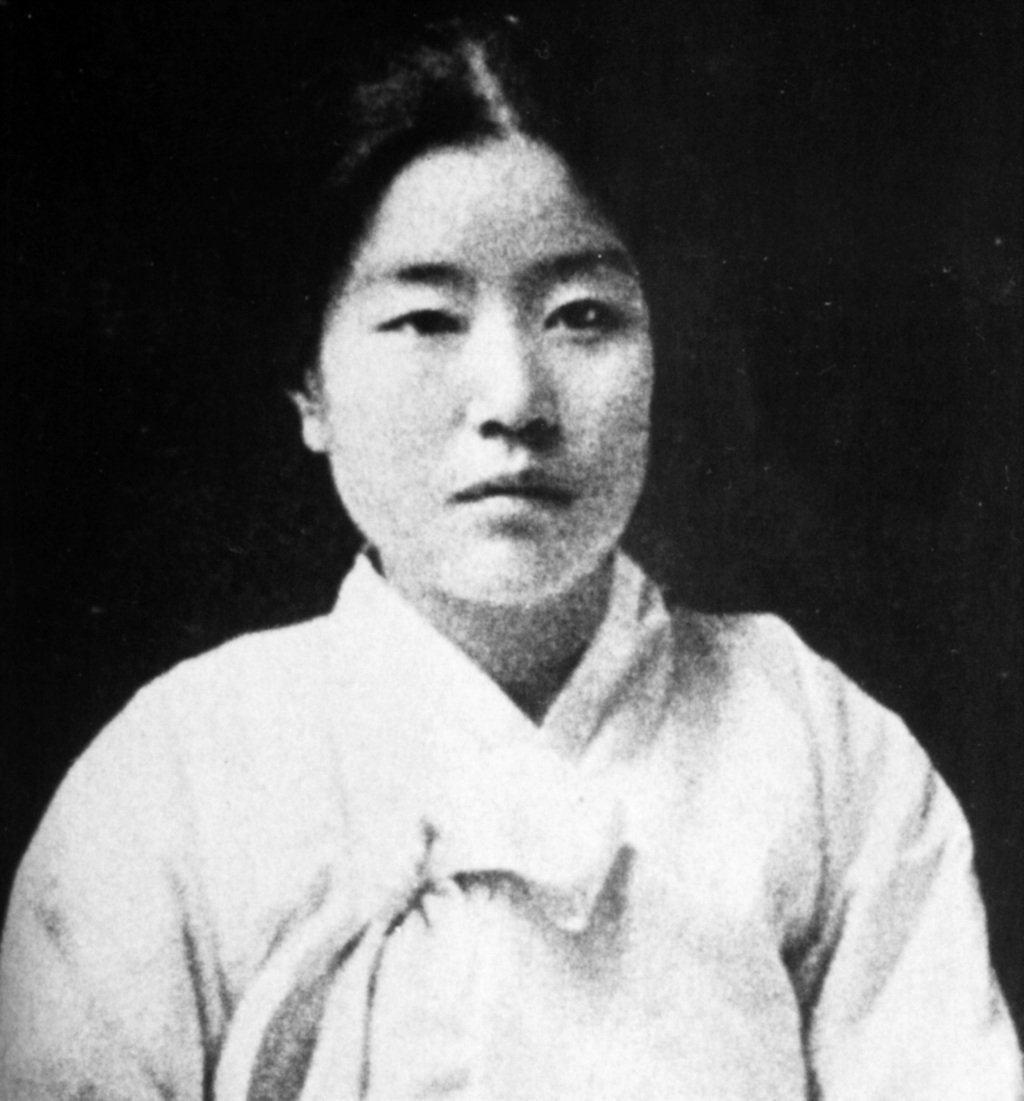

나혜석 | Na Hye-seok

Biography

Of the three women writers who were considered embodiments of the New Woman during the 1920s, Na Hye-seok was the one who transcended disciplines and mediums. Na, who was born in Suwon, graduated from Jinmyeong, the same school that Kim Won-ju and Kim Myeong-sun attended, in 1913. She then continued her education in Japan, where she pursued Western oil painting.

This would lead to Na becoming not only known as a feminist writer in the colonial period but also one of the first professional women artists in Korea. She published her first short story, “Kyonghui,” in 1918, which quickly established her as one of the leading writers advocating for women’s independence, education, and equitable access to opportunities that their male counterparts could easily attain. These beliefs were heavily established during her schooling years, as Na was active in organizing the Association of Korean Women’s Studies in Japan and would be arrested and thrown into jail in 1919 for participating in the March 1st Movement, a major protest movement led by Koreans fighting for the right to self-determination, breaking free from Imperial Japan, and protesting against the poor treatment of Koreans by the Japanese.

Throughout Na’s literary career, her work often took on these subjects and themes, also putting her at odds with the elite literati dominating the publishing scene at the time. Like other writers active during the period, Na received translations, often done from the original language to Japanese, then Korean, of Western writers, which prompted her later literary pieces to take a slant inspired by Western ideals. One piece was her famous 1929 poem “Nora,” which took direct inspiration from Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House” by turning the plight of the protagonist, Nora, into a call to action for women’s rights.

While Na Hye-seok would have some literary success and a major exhibition by 1921, her outspoken beliefs ultimately became her downfall. Na married in 1920 and received funding and support from the Japanese colonial government to tour Europe and

study painting by the late 1920s. By 1931, her marriage dissolved, her husband having filed for divorce under the grounds of infidelity. Already unpopular with the elites due to her outspoken beliefs and advocacy for women’s rights in her work, Na published an essay in 1934 on divorce, sexuality, and how her husband was unable to satisfy her.

This would mark the decline of her literary and artistic career, as the essay was the subject of scandal. It was too radical for the period in which Na published it, leading to her career ending. Like Kim Myeong-sun, Na Hye-seok passed away a decade later, in 1948, in a charity hospital. However, while Na’s work faded, her reputation tarnished, when she published “Kyonghui” in 1918 it established a new period of Korean women’s writing, furthering what Kim Myeong-sun had started in 1917 with “A Girl of Mystery.”

Image Citation: Unknown

Key Dates:

1896 - Na is born in modern-day Suwon.

1913 - Na graduates from Jinmyeong Girl’s High School in Seoul, then moves to Japan.

1915 - Na becomes involved in the Association of Korean Women Students in Japan.

1918 - Na publishes “Kyonghui.”

1919 - Na is jailed for her participation in the March 1st Movement.

1921 - Na has an exhibition of her artwork, making her the first Korean woman in Seoul to do so.

1927 - Na and her husband depart for a tour of Europe, which is sponsored by the Japanese government.

1931 - Na’s husband divorces her, citing infidelity. Na cheats on him in France.

1934 - Na publishes a piece on divorce and marriage, causing controversy. This ends her career.

1948 - Na passes away in a charity hospital.

경희 | Kyonghui

In this short story, the titular character, Kyonghui, has briefly returned home from her studies in Japan. The story opens with Kyonghui and her mother debating with the mother-in-law of Kyonghui’s older sister over the reasons why a girl should study in Japan.

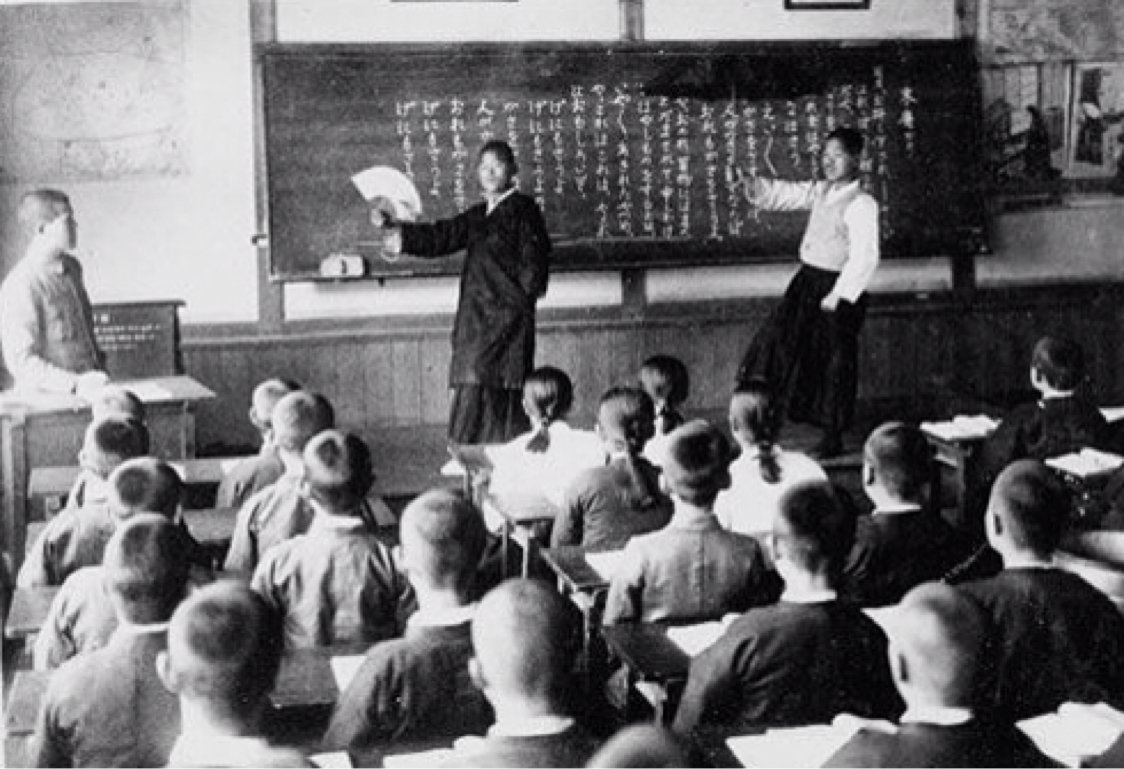

The woman believes this, as told by Kyonghui’s older sister: “girls lose their purity once they go to Japan.” Set in the period in which this story was published (1918), Kyonghui’s education was not a normal story for women.

It was uncommon for women to attend schools, especially abroad in Japan, during the period in which this short story was published, this would make the mother-in-law’s opinions more commonplace than what Na is arguing through the story.

As the story progresses, Kyonghui increasingly decides to live her life outside of gender binaries, exposing how education made her a New Woman, but beyond the stereotypical and popular assumptions that these women were vain and vapid, defying strict moral codes laid out for them by the patriarchal system in place.

Na, who was educated in both Japan and Korea, would become known for doing just this.

Image 1: “Seoho Lake in Suwon,” by Na Hye-seok

Image 2: “Peonies of Hwayeongjeon Palace,” by Na Hye-seok

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis Through KH Coder

In the figure above, the co-occurrence network created 20 subgraphs for “Kyonghui,” although some of these subgraphs were less relevant to the three case studies outlined in this process and showed more basic connections (i.e. “Lady” and “Kim” only reflect Lady Kim’s title). Subgraphs one, six, nine, fourteen, and seventeen were determined to be the most reflective of the goals of the research process. Subgraph one, which is one of the largest clusters in this co-occurrence network, shows the deeply woven connections between Kyonghui and her monologue about how education is a fundamental right for all human beings.

When breaking down the short story in KH Coder, these sentiments are reflected in the co-occurrence networks. One of the most prominent connections is between “Father,” “say,” “what,” “do,” “Kyonghui,” and “be.” Each word is connected by coefficients ranging from 0.11 to 0.15, but they reflect the expectations of Korean women during this period. Although Kyonghui comes from an upper-class household, able to afford to be sent abroad for an education, she believes all human beings can become enlightened when exposed to such opportunities, whether it’s through domestic or international study. Despite Kyonghui’s education status, the third-person narrator mentions how she still works hard, doing all of the chores expected of her as a young woman in the household. It is also mentioned how her mother’s greatest fear was that Kyonghui would become more masculine in her studies, abandoning the traits that she saw embodied a true Korean woman. Even if she was sent away to pursue an education, there is still a hidden fear of what the education could cause for their family’s and daughter’s status in society.

Returning home also means confronting a marriage proposal arranged by her father, suggesting even further that despite Kyonghui debating gender’s limitations and being labeled a woman, her fate is outside her hands when inside the patriarchal system and domestic spaces. At the story’s end, Kyonghui accepts her fate to be within a higher being’s hands, freeing her from the constraints of the time and place she inhabits in the current moment, ultimately allowing her to transcend her situation on an intellectual level. Whether she is successful at pushing this perspective beyond her own is up to interpretation, as the story ends there.

Because of this, like “A Girl of Mystery,” home represents a barrier for the main character. When she is sent home in the summer, there’s a direct correlation between “work,” “sew,” and “summer.” Compared to the monologues Kyonghui ruminates on as she returns to her childhood home, contemplating the role of an educated woman in the world that does not see them for what they are, home represents a more traditional perspective on how her life should be unfolding. It serves as a mirror for what she is doing in Japan, and how, through the chores she is doing and the education she receives abroad, she can become an independent, modern woman.

Throughout the story, Kyonghui interacts with different characters, increasing the occurrence of phrases like “marriage proposal,” and the connection between words such as “marry” and “child.” This language further puts Kyonghui into classifications based on her gender, creating more stark comparisons between her declaration that before she is a woman, she is a human being. With her education, she does not see herself as just a woman. Instead, she is an enlightened human.

Regardless, despite a significant portion of the story being propelled by discussions on her life abroad while studying in Japan, there are few links to this experience to the act of doing work outside learning. The passive verb “learn” is most associated with this specific experience, and it highlights how she intellectually and humbly interacts with a wide variety of characters, from the family maid, mother-in-law, and a rice cake peddler who arrives to sell her wares. Each main character she interacts with has their own function and works to serve not only within the household, mirroring Kyonghui’s experiences and how they’re interpreted by others.