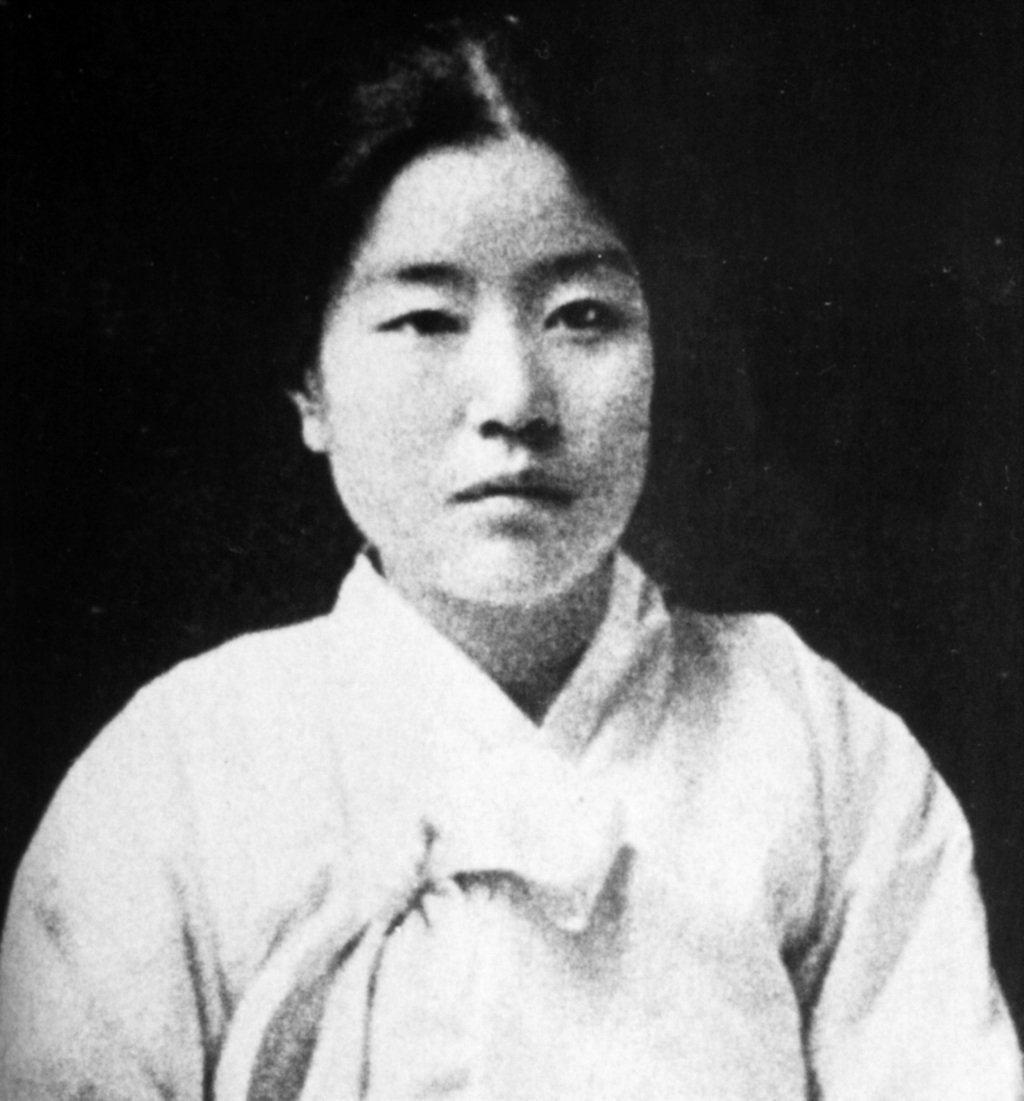

김명순 | Kim Myeong-sun

Biography

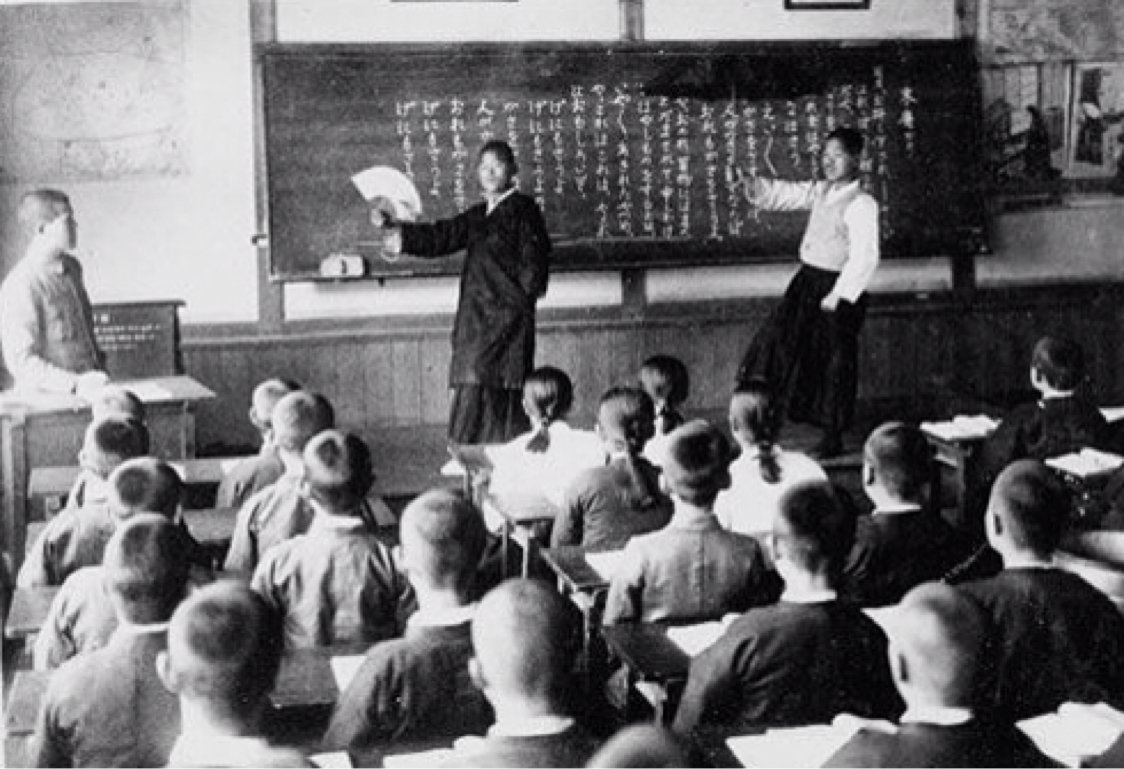

Born in Pyongyang, Kim Myeong-sun was given several key opportunities early on in life. Her parents sent her to Seoul to study at a girls’ school, which would be the same school Kim Won-ju and Na Hye-seok would study at. Both of Kim’s parents died after she moved to Seoul, which, according to Choi Jung Ja, would form a trauma that manifested in her later works. However, after her initial education in Seoul, Kim moved to Japan during the 1910s to further her studies, but she did not finish her education there. She returned to Korea, received her degree locally, and then embarked on her career as a writer and translator.

Despite having left Pyongyang and her family behind as a young girl, the shadow of Kim’s mother hung over her wherever she went. During her primary education years, Kim was bullied because she was the daughter of a kisaeng, or a courtesan trained in the arts. In the hierarchy of Joseon society, kisaengs were considered to be cheonmin, or one of the lowest social classes, despite the fact these women were highly trained in the arts and literature. While some kisaeng were able to gain some autonomy during the colonial period by facilitating and participating in the sale of exotic postcards, which featured the kisaengs in Western and traditional Korean attire, the stigma remained.

Despite this, Kim Myeong-sun is a writer who made Korean literary history twice: “A Girl of Mystery,” published in 1917, is considered to be the first piece of literature published by a modern Korean woman writer, while in 1925, her collection The Fruits of Life, was the first by a Korean woman. Her writing appeared across genres, some even blurring the conventions of genre to become something in-between, which is a common form of radicality that appeared throughout her artistic career.

Throughout her writing, Kim fought against the male-dominated systems that she lived inside, as argued by Choi Jung Ja, introducing #MeToo a century before it would become recognized and popularized, and wrote about notions of free love and independence. Her work often took on a semi-autobiographical tone, and, later in her career, she even began writing poems in what is now considered to be the confessional literature genre, which would become more prominent in the American literary scene during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

It was this radicality that opened her up to criticism, despite writing under several other pen names, and her career ended by the late 1930s. Kim was often the subject of gossip, and several male Korean writers, such as Kim Ki-jin and Yom Sang-seop, openly criticized her and the works she published due to the ideas and themes she presented within them.

These critiques often leaned personal, using ad hominem arguments against Kim’s background and life to try and take her down. She addressed the criticism both directly and indirectly, but it did not save her reputation in the long term. 1939 would be the last year Kim Myeong-sun published any creative work. Throughout her career, she published poems, plays, short stories, novellas, and essays, and, in the last years of her writing life, she increasingly became autobiographical and personal. Unable to provide an income for herself anymore, she died in 1950 without anything to her name.

Image Citation: Kyobo Books

Key Dates:

1896 - Kim is born in Pyongyang, then Joseon, now North Korea.

1908 - Kim moves to Seoul in order to pursue an education.

1913 - Kim moves to Tokyo for the first time, and her parents have passed away. Soon, she moves back to Korea.

1917 - Kim publishes “A Girl of Mystery.” It is the first work of literature published by a modern Korean woman.

1920s - Kim continues publishing short stories, poems, dramas.

1938 - Kim publishes her last works.

1951 - Kim passes away at the age of 55. She is penniless and destitute.

의문의 소녀 | A Girl of Mystery

In “A Girl of Mystery,” the “girl” in question is Pomnye. She lives with her grandfather and a maid, and the local villagers consider her to be quite beautiful. She is also the source of mystery: her grandfather has forbidden her from going outside and interacting with the locals, leading to her living a lonely lifestyle for a young girl.

Over the course of the story, we learn why this is the case. Pomnye’s mother killed herself after learning her husband was cheating on her, and Pomnye’s maternal grandfather took Pomnye away from the situation.

Pomnye’s grandfather forbid her from venturing outside of the home, as her father, a wealthier man living in Seoul, is actively looking for her after her mother’s suicide.

Pomnye’s mother’s suicide is a radical act, one propelled by the character’s need to take back control of her life and protest against her husband’s infidelity, even if it casts a long shadow over her daughter and legacy.

She is not a Joseon-era yeolnyeo, but the extent of her husband’s actions—and, by a larger extent, the patriarchy—has led to the destruction of not only her life, but her daughter and father’s lives as well.

He changed her name, and ever since then, they have been on the run. However, Pomnye and her grandfather are forced to leave the village, as her father is still looking for her. The novella ends with Pomnye waving goodbye at one of the only friends she made in the village, forced to relocate yet again.

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis Through KH Coder

The figure above demonstrates the co-occurrence network created for “A Girl of Mystery.” In it, 14 subgraphs were created, with certain subgraphs containing larger clusters of words than others. When looking at the co-occurrence network holistically, I first determined which words were directly connected to Pomnye and the family unit, which were subgraphs one, two, four, and five. The red circles in Figure 2 demonstrate key areas of focus throughout this project: the family unit, the concept of home, and the association between “wife” and “death.”

When utilizing KH Coder to break down “A Girl of Mystery,” some of the strongest connections between individual words and phrases mirror the connections between characters. In one cluster, Director Cho, who is Pomnye’s estranged father, has a direct correlation to the word “daughter,” which has a coefficient of 0.21 and a higher frequency than related words. Although Director Cho does not make a physical appearance in the world of the story, his presence looms over the narrative, especially as the other villagers gossip about Pomnye’s true origins and how her father has been looking for her. An assumption made is that if Pomnye stayed with his new family, she would not be treated properly.

The previous two words and phrases are also linked to the word “marry,” which compliments another two clusters: “curiosity” and “family” are suggested as having a stronger link, with a coefficient of 0.29, as well as “poor” and “child,” which relate to a coefficient of 0.40. Throughout the story, Pomnye is both a source of fascination and pity. Despite having an appearance considered to be lovely by the other villagers, like someone who has come from a city, Pomnye is not allowed to interact with other girls her age, nor leave her home.

An emphasis on her being a poor child stuck in a cycle of grief, perpetuated by the systems dominated and created by the men in her life, both subverts and feeds into the stereotype that the situations women and girls find themselves in are a byproduct of han. Because of the tragedy in Pomnye’s life, she has become defined by it. However, this tragedy can be interpreted as a major critique of the patriarchal systems in place. While Pomnye is left lost, without a mother and father, her birth father has benefitted from the systems in place without any major consequences.

The language of the story itself reflects the loss: “mother” appears in the short story only four times, while “wife” appears 11 times in various contexts throughout the text. This may be, in part, due to how the story is told. A third-person objective view allows readers to come to understand the greater details from those not directly involved with it; gossiping women relay the crucial details of Pomnye’s backstory, filling in the blanks and gaps as necessary.

The co-occurrence network also offers another suggestion when it comes to the concept of home for Pomnye and her grandfather: the words “neighbor” and “goodbye” are inherently linked, even if the physical act of leaving does not happen until the end of the short story. The concept of a home in “A Girl of Mystery” is a turbulent one; due to the nature of Pomnye’s situation, her grandfather decides to move her when the possibility of her father coming to find her arises. As seen in Figure 2 with KH Coder, a home is often associated with her grandfather’s presence, as well as the word “gate,” implying a sense of feeling trapped within one’s situation.