via the Korean Film Archive:

경성소식 (1920년대 추정) | Gyeongseong News (1920s)

Case Studies

-

Domestic Spaces

How is the home being represented in a specific way? Is it limiting the protagonists, or a place where creativity and ideas are fostered?

-

Women's Work

What are the depictions of labor in these stories? Are they, too, being depicted in a flattering light?

-

Han & Female Suffering

Han is often defined as a uniquely Korean form of suffering. How are women subverting and using depictions of suffering in these stories?

Case Study 1: Domestic Spaces

The concept of “home” and what it entails appears throughout each short story in different forms. On one hand, this is highly unsurprising: throughout the colonial and postwar periods, women, if allowed the privilege, were expected to remain housewives and merely do chores within the home. This reinforced the Joseon-era belief systems about what women could and could not do, especially those from the upper classes, or the elite yangban, the aristocracy, of Korean Confucian society. As women from the elite yangban class may have been allowed more financial and social privileges during their lifetimes, including the fact they were able to access literature and have the means to learn how to read, they were more limited than those coming from lower socioeconomic statuses in their movement and how they could present themselves to others.

Looking at KH Coder throughout the six short stories, personal and domestic spaces are stifling for the main characters and protagonists. Whether it’s a demeaning husband who refuses to acknowledge his wife’s budding literary career, putting her down whenever he gets the opportunity, or not having a real space to call a home as an estranged father relentlessly searches for his lost daughter, the home becomes a liminal space that straddles old and new ideologies.

In a short story like Han Moo-sook’s “Hydrangeas,” this becomes more obvious with the heavy-handed symbolism of the hydrangeas planted outside the home. In the beginning, these flowers represent the hope of a new marriage and what it might fulfill, as they were brought into the home after the protagonist married her husband. However, by the story’s end, they are bathed in moonlight, having transitioned into a painful symbol representing that lost hope.

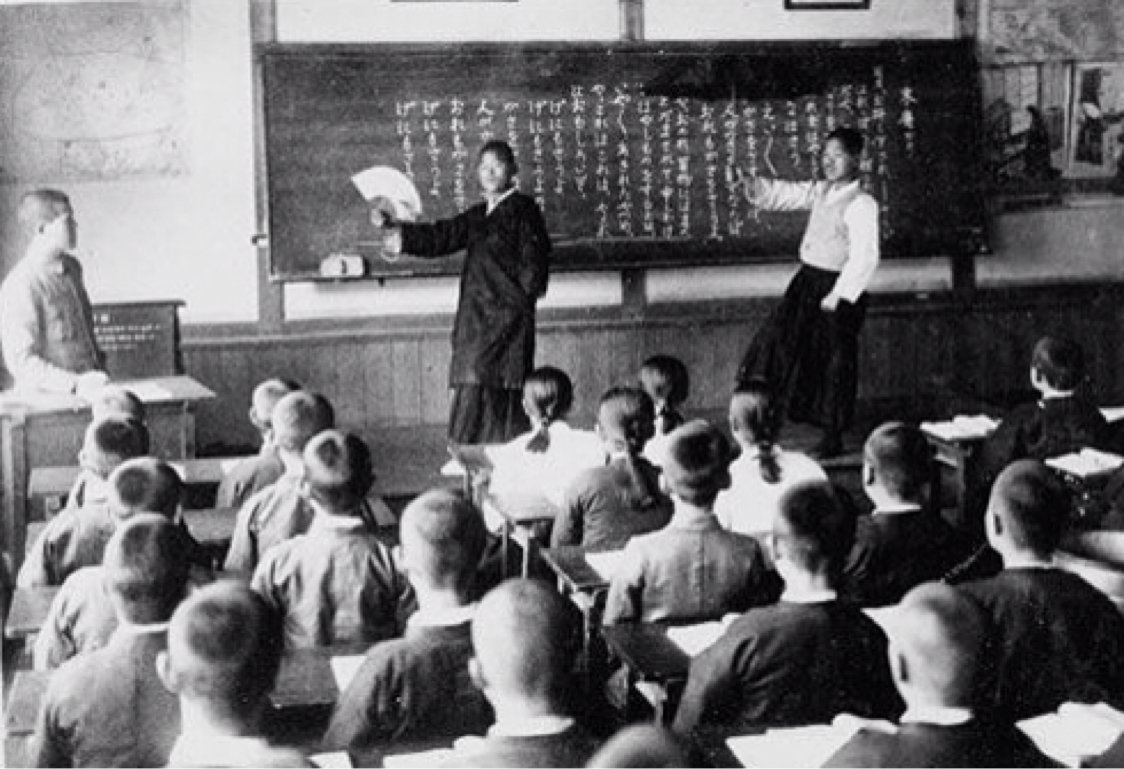

With Japanese colonization, women were, for the first time, given the opportunity to attend school. While schools like Ewha Girls’ School, often run by American missionaries, were created at the end of the 19th century, these spaces outside the home would allow them the opportunity to be presented with a Western-style education and ideas they would not encounter in their personal and social spheres. Going abroad to Japan was also only available to a select group of Korean students, essentially locking out anyone who was from a lower class or socioeconomic status from pursuing education abroad unless they were able to garner sympathy from a wealthy benefactor. In addition to this, those being educated in Japan often became active in advocacy groups, much to the Japanese government’s chagrin.

Except for Kim Myeong-sun’s protagonist (Pomnye in “A Girl of Mystery”), who is stuck in a flux of fleeing from one place to the next, the protagonists have been exposed to some sort of education, ultimately reflecting the attitudes and class privilege of the writers who created them. For example, the main character in “Awakening,” which was published in 1926, conveys her story through written letters back and forth between two friends. This directly implies that both women have had the opportunity to be somewhat educated, thus learning how to read and write.

In “When Autumn Leaves Fall,” the main character spends time wandering around an art gallery, and even meets with her first love in a tearoom. There are several moments in the story where she returns into the home she shares with her husband and children, and when she arrives back at this space, it immediately reminds us within the narrative how she feels drained and left behind by her domestic life. She spends most of the story wallowing between past and present, trying to figure out where her life took a turn.

Unable to connect with her children anymore, and dealing with a husband who cheats on her, coming home literally evokes dread and further disappointment with her life. Despite having some success in the art world, the main character’s limitations and insecurities partially stem from her home life, which is a consistent theme throughout each of these stories. In “Kyonghui,” the protagonist denounces the gender she is being interpreted and seen as within a dramatic monologue, ultimately deciding she is neither female nor male at the end, a conclusion she reaches because of her education and the circumstances she comes home to.

Taking the arguments made by Korean women activists in the 1910s and 1920s a step further, these stories suggest girls and women can receive their education and achieve one form of liberation from it, but to be truly liberated from the systems in place, they need to have a place of understanding beyond the systems rooted in the patriarchy. The home becomes a place of limitation, as seen in its various connections within KH Coder. Whether it’s a gate, which may symbolize being kept inside the space, whether by choice or not, or associating it with hydrangeas that represent a dying marriage and faith, these writers are depicting homes as a space where women lose the confidence that defines them as someone beyond the label of “woman” and “wife.”

The Housemaid (1960)

Kim Ki-young’s 1960 movie The Housemaid embodies several characteristics of all three case studies.

Case Study 2: Women’s Work

The expectations of Korean women up until the final piece’s publication, “When Autumn Leaves Fall,” in 1961 would remain consistent up until the postwar period, especially for these writers, who would consist of an upper-middle-class elite. In the six short stories, they feature female protagonists who reflect these backgrounds: they are housewives, students sent abroad to study in Japan, and a young girl taken away from her father after her mother’s death. “Work” is a common verb that consistently appears in each of the short stories’ analyses, with its connected words varying, but hitting on similar thematic notes.

However, in the context of these stories, “work” almost always manifests as a form of domestic labor. In “Kyonghui,” this appears as Kyonghui comes home and dutifully performs the chores she was expected to do even without her education. This shows her mother that she hasn’t become too masculine and forgotten who society thinks she should be. In KH Coder, this reveals itself through how interconnected the word “educate” is with both “girl” and “men,” exposing Na’s overall plea and agenda that education is for everyone.

In a story like “The Mist,” written by Kang Sin-jae, this occurs in its most direct form. The protagonist is consistently held back by her husband, envious of her success and unable to acknowledge that his wife, a woman who primarily works and lives as a housewife, is more successful than him. “Work” for her is separated into two completely different categories that are assigned by gender: her work as a woman includes being a housewife and doing all the necessary chores in their daily life, but she wants to continue pursuing a more masculine form of work.

Again, “A Girl of Mystery” is an isolated example. Because of the narrative’s structure, many core events are told through a third-person subjective that doesn’t go in-depth about her daily life. For example, it is not told what really happened until the villagers are watching her leave the area with her grandfather. Then the third-person narrative opens with the description of who she once was, as well as the name she was born under before being rebirthed as Pomnye.

She is the youngest protagonist, the only one still a child, and the unique circumstances of her situation can explain the absence of associating her with women’s work and labor, as well as the fact her grandfather enlists a maid who comes with them as they travel around, avoiding the wandering gaze of Pomnye’s real father. However, Pomnye’s fate is sealed with her mother’s death, creating turbulence due to lacking a female, maternal figure doing that form of work in her life.

Throughout several co-occurrence network graphs created, one particular string of words kept appearing: “be,” “not,” and “do.” Often, they occurred in a scenario where they had a higher frequency, creating a conceptual reflection of the beliefs that women could not do things, but instead simply exist as they were told to do. “Be” appears in several stories, sometimes not connected to “not” and “do,” but typically in correlation with the female character and her husband.

These words reappearing throughout each text, even when published several decades apart, imply a sense of agency has been lost among these women. When connected specifically with the main male figure in their life—typically their husbands, or, in Pomnye’s case, a grandfather—it creates a more direct link between how their lives are dictated by those who hold more power. “Work” is typically associated with household chores, not going out and pursuing creative endeavors or holding a job for these women, who typically are from upper-class backgrounds.

“The Mist” directly personifies this concept with how the protagonist, a woman finding herself some success as a writer and wanting to provide for her family when her husband cannot, finds her work being intentionally sabotaged by her husband. Instead of pursuing more work and generating an income, it would be shameful for her to pursue a job, even if intellectualism and putting them within the sphere of cultural elites. To complicate things even further, the fact his wife is more successful than him creates a deeper layer of shame, threatening his reputation, and by extension his masculinity, even further.

Popular movies, now classics in the Korean cinema canon, like Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid in 1960, may mark a shift in how less privileged women were beginning to enter the workplace, especially as they began working in factories again. Even in The Housemaid, purchasing a home is depicted as an aspiration for the rising middle class in South Korea, but for its characters, especially the women, who are the only survivors of the carnage about to ensue, it becomes a source of suffering and trauma.

Perhaps, if even one of these writers came from a background that would not allow her to be a prominent writer in colonial and postcolonial Korea, the results of this study would have differed. When looking at factory girl literature that was published during the 1920s, some of the stories that made their way into discussions and discourse were about sexual assault and the poor conditions of the factories these young girls and women were working within. Pieces from the kisaeng literary magazines and publications from the period, too, would look at the unique problems these women faced throughout their careers.

Case Study 3: Han

Under the systems of belief that the concept of nation-building is a masculine one, with the traditional Confucian beliefs co-opted and reinvented for modern women, the closer examination of these six works takes on new meanings. When looking at texts like On the Eve of the Uprising, which compiles the short stories of several male writers working within the colonial period, women often fall under similar tropes that echo classical Joseon representations: the filial wife, self-sacrificing daughter, fervent believer, and devoted lover. The women who appear in these short stories play a specific role, but their endings might not be ones they would personally desire, as they are at the male protagonist’s whims.

Referring back to the example of Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid, now considered a classic in contemporary South Korean cinema, a factory worker is enlisted in the house of a middle-class family as a maid, but seduces the husband and becomes a source of suffering, death, and the rupturing of a traditional family unit. As the maid stands nude in the shower, the family’s patriarch watches her hungrily, separated from her only by the shower’s glass, making her a physical embodiment of sin and a devil. Perhaps, in another world where she did not enter the lives of this newly middle-class family, they would have continued to live blissfully within their newly purchased home.

As the concept of the nation and Korean independence was formulated with masculinity in mind, male writers were leaning towards depicting women as a physical embodiment of han. Korean men were expected to be leaders, so the failure of Korean leadership and masculinity can create a cycle in which women are suffering. While this is one suggestion as to why the male writers in On the Eve of the Uprising might be depicting women in such a negative light if they were to appear in these stories at all, the six stories in Questioning Minds offer a different insight into how the patriarchy might be failing women.

During the colonial period, the concept of han was initially formed. Now something adopted by Koreans and their diaspora, han has been defined as the unique sorrow of the Korean people, and how, in recent history, there has been an abundance of suffering when it comes to contemporary issues and the long-term impacts of colonialism and war. This has been criticized due to its roots within the Japanese colonial system, but throughout modern Korean literature, it can be argued that female characters are being used as an extension of han. As they are expected not to have agency over their decisions and control over might be able to happen to them, this perpetuates the system in which the masculine nation’s failure has led to this suffering.

Throughout the six stories, the female protagonists’ unhappiness becomes increasingly obvious even without the use of a text mining tool like KH Coder. Each story’s main character finds herself bound by the deeply patriarchal systems in place, even if she finds success intellectually abroad in Japan, or as a writer in Korea who has just started to get published in literary journals. This manifests in how the co-occurrence networks show how these women are directly connected to the male characters, often their husbands, which is a consistent theme.

However, it would diminish these women’s writing to say they solely depict women vehicles for han and suffering. Subverting the “suffering woman” plays a key role. It appears with Kim Myeong-sun’s protagonist’s mother choosing to kill herself, an act considered highly shameful, in “A Girl of Mystery.” As seen in the recurrence of the word “break” and its significance in a story like “Hydrangeas,” there is a clearly defined before and after for many of these female protagonists, even though they may not be aware yet.

While factory girls and female bodies were being used to further the idea of a Korean nation and cult of masculinity, han also offered a different alternative: a sense of peace and community. Sandra So Hee Chi Kim defines this as a “transcendence,” something that not only defines a unique sense of Koreanness but an indicator that builds a larger community where one has the opportunity to tell their story and engage with others who faced similar experiences. As Bassnett proposes the idea that the translation of writing allows one to engage with trauma through a removed lens, the act of writing in itself can also serve as artistic therapy and community building for these writers and creatives. While han specifically defines and limits itself into something uniquely Korean, becoming an indicator of a community, its subversion in the feminine context allows a new opportunity to explore deeper into how women were not identifying with the cultural elite’s main benchmarks and ideologies. For those writing within the colonial period, they often worked and engaged with each other’s works. Na Hye-seok and Kim Won-ju are cited as not only having been published in the same journals together, but also working within the same literary spheres and publications. In the postwar era, writers like Song Won-hui and Kang Sin-jae served on the leadership of women’s literary organizations in Korea, demonstrating how broader connections are made within female-dominated literary spheres.

This ultimately allows and empowers these women to create opportunities due to these networks, as seen with the kisaengs who continued to publish and create literary magazines after Joseon’s annexation. In the modern day, the act of translating these works continues to create a larger community across periods and borders, creating conversations about connection. This subverts not only han, but also the idea that the home is a place where a woman remains by herself. While male writers are engaging in the practice of han as something to depict women as a product of suffering, and potential failures of masculinity, women writers were instead creating conversations about what it means to feel trapped inside circumstances beyond their control.