Heroines by Kate Zambreno

Review of Heroines by Kate Zambreno

“I am beginning to realize that taking the self out of our essays is a form of repression. Taking the self out feels like obeying a gag order—pretending an objectivity where there is nothing objective about the experience of confronting and engaging with and swooning over literature.”

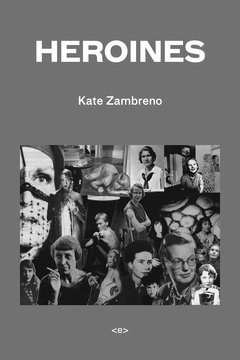

Heroines by Kate Zambreno (2012). Published by Semiotext(e).

I had never heard of this book or even of Kate Zambreno before until I joined literary Twitter as a somewhat active citizen. It was stumbling upon Zambreno’s website and admiring her haircut (I really loved the blunt bags she had as her picture, I’m a sucker for blunt bangs) then realizing she’s actually a very established writer.

As in she is a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow for Nonfiction and has taught at both the writing programs at Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University—two very good writing programs. And thus I was immediately curious about her body of work and downloaded almost all of her books for a rainy day.

Now I didn’t read anything about this book particularly before starting it and it was the first of the stack of Zambreno books I had to get through. I thought it was feminist-based because of the various women writers depicted on the cover, but I was also confused because this was classified as creative nonfiction. It took actually cracking open the book and digging deep into the universes created by Zambreno for me to understand what was actually happening here. Let’s start the review.

Where the women writers of the 1900s meet one modern woman: Kate Zambreno.

You’re probably very confused by that header I’ve put above this. But no worries, I’m here to save the day. This book was apparently inspired by a blog that Zambreno started in the early 2010s about women writers who had shitty men in their lives, despite the women themselves being these awesome modernist writers that were held back because of their gender.

The women often mentioned in this novel are Zelda Fitzgerald, Vivienne Eliot, Jane Bowles, and Jean Rhys. Going into this, I was already familiar with every single one of these writers, so I was a tad bit bored when Zambreno was launching into these descriptions about how and why they were oppressed. I already knew these facts.

What’s interesting about this book particularly is that Zambreno weaves in the tales of these women to her own life. I genuinely did not care for a chunk of these portions because of how privileged the author comes across as. Like we get it, you can be a writer who has sex and your husband has a cushion-y professor job.

Her complaints of being treated as a sidepiece woman to the man’s intellect are completely and utterly valid, but, at the same time, it is what allowed her to get where she is today. Zambreno probably would not have as much free time to write as she did without this paycheck unfortunately. And that’s the reality for most writers.

While the experiences of the women she discusses are also valid, there’s something glaringly obvious if you know these women or go and look them up in between reading the pages. Every single one of them was white and also lived a privileged life. You can argue that some like Zelda Fitzgerald wasn’t exactly living the high life, but you also have to think of where she came from: rich Alabama. She was literally a rich socialite. I think maybe I would’ve been a tad less frustrated with this if Zambreno didn’t rehash the same core concept (oh my god, they’re oppressed and their creativity is suffering because of it) again and again.

I think I’m also frustrated with this being rehashed because Zambreno is comparing herself to Virginia Woolf and Zelda Fitzgerald. I don’t think she gives herself the agency to make these comparisons to women who suffered from major mental illnesses and were straight up a lot more oppressed than she was. She talks about how sexist it is to criticize certain things that lean towards a more feminine audience, but then also scoffs when like her neighbor gets a Martha Stewart magazine. I think that’s also very sexist.

Zambreno is a good writer, that’s for sure. I just don’t think this topic was good territory to insert yourself into a narrative. Like I wholeheartedly agree with her in the fact that the men of the Modernist period, like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, were honestly kind of trash, especially to the women in their lives. But this book comes across as having a holier than thou attitude that seems to determine what can and can’t be feminist.

It comes across as false enlightenment, when I personally skewer towards the belief that feminism can be whatever it wants to be for the person wielding the power, e.g. the individual. It’s the power for women to choose their own destiny and accept that other women would choose to be or not be something. Although we do need to have an understanding of how certain quote-on-quote traditions came to be and are imposed, so we can make these decisions in a more informed manner of why we’re choosing what we’re choosing.

Overall Thoughts

I don’t think this book aged well at all. In an era in which we’re talking about intersectional feminism, it doesn’t feel too good to be a BIPOC woman reading about the white woman I’ve always seen in the narrative. Especially as I go and do more research about women writers in the early 1900s, these idols of Zambreno only scratch the surface.

Where is Natalie Clifford Barney, the lesbian poet and playwright who made sure that women writers were championed? There were so many big lesbian women writers who supported each other: Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, etc. There’s so much deeper history in the world of women’s writing, so it felt a bit disappointing to see only the vast majority that are usually mentioned be mentioned again and again.